An Insider Attack on the eCommerce Industry

CYBR650 Research Paper

Glenn Ford and Zack Rich

UMBC Cybersecurity M.P.S.

CYBR650 - Managing Cyber Operations

Dr. Robert R. Romano

April 29, 2014

1.0 Executive Summary

2.0 Scenario

3.0 Discussion and Findings

3.1 Details of the Attack

3.2 Forensics of the Attack

3.2.1 Legal Issues In Forensics

3.2.2 Digital Forensics Team

3.3 Costs of the Attack

3.4 Lessons Learned

4.0 Recommendations

4.1 Incident Response Planning for Insider Attacks

4.1.1 Preparation

4.1.1.1 Cybersecurity Insurance

4.1.1.2 Legal Considerations

4.1.1.3 Insider Threat Mitigation Program

4.1.1.4 Educating Employees

4.1.1.5 Designing and Instrumenting Networks

4.1.2 Detection

4.1.2.1 Host-based Detection

4.1.2.2 Network-based Prediction of Malicious Behavior

4.1.2.2.1 Applied Behavior Analysis

4.1.2.2.2 Automated Behavior Analysis (AuBa)

4.1.2.2.3 Using Inmate to Identify Insider Threats

4.1.2.3 Using Honeypots to Detect Insider Threats

4.1.3 Containment

4.1.4 Eradication

4.1.5 Recovery

4.1.6 Follow-up

4.2 Improving Technical Controls

4.2.1 DLP/ILP Suites

4.2.2 Discovery and Classification Tools

4.2.3 Database Security

4.2.4 Application Entitlements

4.2.5 Removable Media

4.2.6 Defensive Search

4.3 Implement/Improve Administrative Controls

4.3.1 Administrative Policies

4.3.2 Personnel Clearances

4.3.3 Employee Communication and Training

4.3.4 Database Baselines and Best Practices

4.3.5 System of Record Audits

4.4 Future Mitigation Strategies

4.4.1 Early Mitigation Through Setting of Expectations

4.4.2 Handling Disgruntlement Through Positive Intervention

4.4.3 Eliminating Unknown Access Paths

4.4.4 More Complex Monitoring Strategies

4.4.5 Risk-Based Approach to Prioritizing Alerts

4.4.6 Targeted Monitoring

4.4.7 Measures upon Demotion or Termination

4.4.8 Securing System Logs

4.5 Ensure Testing, Training, and Exercises

4.5.1 Testing, Training, and Exercises Policy

4.5.2 Identify Roles and Responsibilities

4.5.3 Establish Overall Schedule

4.5.4 Document Methodology

4.5.5 Training, Exercises and Tests

4.6 Ensure Incident Response Plan Maintenance

5.0 Conclusion

References

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

Appendix G

Appendix H

Appendix I

Appendix J

Appendix K

Executive Summary

RichFord Retail Group (RFRG), based in Rockville MD, is a sporting goods eCommerce retailer. RFRG, founded in 2001, currently has 410 full-time employees and 2013 annual revenue of $300 million. RFRG maintains and supports over 10 million customer records powered by a proprietary Just in Time ordering system.

RFRG was a victim of an insider attack by a disgruntled employee who was denied a promotion. The employee, using authenticated and authorized access, has exfiltrated personally identifiable information and confidential company information. The attack has caused severe financial damage and loss of online reputation, which lead to a substantial drop of 2014 revenue. Prior to the incident, RFRG has implemented an Incident Response Plan, technical and administrative controls to detect and mitigate external threats, but never properly addressed internal threats, whether malicious or incidental. At the heart of the problem is knowing the enemy and to predictively assessing an insider threat is going to occur before it actually does.

The best approach for detecting insider threats is a multi-layered and defense in depth strategy. A comprehensive list of recommendations is provided to enhance the existing Incident Response Plan, technical controls, and administrative controls. Future mitigation strategies are discussed in depth specific to insider threats. Network-based automated behavior analysis can help identify anomalies and other patterns of human and computer behavior that signal new and unknown threats before the threat occurs with validated measurements of intent and deception. This advanced network-based automated behavior analysis technology is based on the InMate Network Misuse Detection System and is a vital part of the overall multi-layer and defense in depth strategy. The solution to mitigate insider threats does not involve one technology or strategy. It involves many technological layers of security combined with non-technology strategies.

Insider attacks account for about 69% of all information security attacks (Berinato, 2007, p. 4) and if organizations do not perform insider threat surface reduction, the consequences can be catastrophic. The RichFord Retail Group insider attack scenario serves as a model of the possible consequences a company could face if not properly prepared.

Scenario

This scenario contains fictional information regarding the background and current situation of an insider attack on RichFord Retail Group carried out by John Doe (see Appendix A for Company Profile). John Doe has been employed with RichFord Retail Group since 2009 as a Sr. Systems Administrator and a Deputy Director of Operations. His job role and responsibilities required him to have access to the customer database servers, accounting servers, and sales systems. In May, 2013, John Doe was denied a promotion to the Director of Operations position and expressed frustration with Human Resources (HR) and executive management. On February 13, 2014, the IT Audit Department discovered a 1 gigabyte encrypted ZIP file on John Doe’s workstation. The file was determined to contain PII and company confidential data. After incident investigation was completed, John Doe was terminated on March 3, 2014. RichFord Retail Group is currently working with local and Federal law enforcement officials. All customers have been notified and offered free one-year of identity protection service. See Appendix B for a full list of assumptions as part of the scenario and this paper.

Discussion and Findings

The insider attack carried out by John Doe caused severe damage to RichFord Retail Group in terms of lost revenue due to negative reputation, lawsuits, and loss of existing customers following the incident. It is critical for RichFord Retail Group to evaluate, analyze, and improve security to combat emerging insider threats. Discussion of the John Doe insider attack will be examined in the following four sections: (1) Details of the attack; (2) Forensics of the attack; (3) Costs of the Attack; and (4) Lessons learned.

Details of the Attack

Upon further investigation, the Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT) was able to brute-force crack the password and discovered that there were three files contained in the ZIP file that was on John Doe’s work computer. The ZIP file, located on the Desktop, was named as “miscellaneous.zip”. The first file contained 1,020,031 customer records stored in a Comma Separated Values (CSV) file. Each customer record contained their name, shipping address, billing address, order history, phone number, and credit card information. The second file contained company finance records dated from July 3, 2012 to December 29, 2013. The last file contained proprietary source code for the RichFord Retail Group Just in Time (JIT) sales system. JIT is a production level strategy that keeps in-process inventory low to reduce the associated carrying costs, thus improving on the business’ return on investment. CSIRT’s investigation also revealed that outgoing network traffic from John Doe’s workstation had numerous spikes between July, 2013 and January, 2014. Outbound network activity logs showed that John Doe’s workstation used Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) port 80, Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) port, during the network traffic spikes. CSIRT’s investigation concluded that PII and company confidential data had been exfiltrated through the RichFord Retail Group’s network to an IP address in Bangalore, India during these network activity spikes. Investigation of internal server to workstation network activity on John Doe’s computer showed no unusual anomalies (see Appendix C, Figure 1: RichFord Retail Group Network Topology Overview). CSIRT audit logs showed no files were copied to removable media, such as USB, during the incident period of May 1, 2013 to February 13, 2014.

Forensics of the Attack

Digital forensics of the insider attack on RFRG was performed by the Forensics team to assist in root cause analysis and used established methodologies from NIST SP 800-86 to assist in the collection of legally defensible evidentiary material to assure proper handling and presentation of evidence (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 322-323).

Legal Issues In Forensics

The Forensics team followed the corporate guidelines to assure evidentiary material could be admissible in any future legal proceedings. The procedure employed included the following conditions: (1) Verification of corporate policy to allow a search; (2) Justification of the search at its inception; (3) Assurance that search has a specific focus and is constrained; (4) Clear ownership of searched devices and other containers of material; and (5) Proper authorization by senior management for the search (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 323-324).

Digital Forensics Team

Forensics was done in two stages starting with the first response team that collected useful information, taking into consideration the volatility and effort required to copy the information through imaging. All work done is photographed and records written about every step. Once an image is created it is logged in a field evidence locker. Once all images are stored, the second stage can begin, which is the analysis and presentation. Analysis used the digital forensics analysis methodology (see Appendix D, Figure 2: Digital Forensics Analysis Methodology) as defined by the United States Department of Justice. The results of the forensic analysis were presented to senior management and legal departments (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 333).

Costs of the Attack

Insider attacks, such as those done on RichFord Retail group, are devastating financially, have a negative impact on reputation, and result in loss of existing customers. In a survey of organizations with insider attacks, 75% of organizations have reported a negative impact on their business operation and 28% reported a negative impact to their reputations. The costs can run into the tens of millions of dollars (Baracaldo and Joshi, 2012, p. 167). A federal court in New Jersey has agreed with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) that it is allowed to sue companies for data breaches (Vijayan, 2014). Laws will continue to evolve on the side of protecting PII and other sensitive data that can harm customers or other 3rd parties. Companies need to increase their cybersecurity and information assurance posture. Companies that postulate about having adequate security and due diligence will no longer be enough, given the FTC ruling and the future evolution of cyberlaws to protect sensitive data.

Loss Analysis needs to be performed to determine total costs and should include: (1) Costs of people hours to react to incident; (2) Costs of people hours to recover data; (3) Opportunity costs for people hours lost not being productive because of incident; (4) Legal costs associated with prosecuting offenders; (5) Legal costs for lawsuits against RichFord by customers and other clients such as credit card firms having to re-issue new cards to impacted customers; (6) Costs associated with loss of market share and advantage from proprietary JIT software disclosure; (7) Costs associated with additional security as per recommendations before budget cycle (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 321). RichFord Retail Group’s loss analysis also needs to cover costs for identity theft resolution.

Lessons Learned

Lessons learned clearly show RichFord Retail Group was not properly prepared for an insider attack of any size, much less one as devastating as that executed by John Doe. The implemented security controls and Incident Response Plan were both designed to prevent infiltration from external threats, while internal threats had little to no detection or mitigation countermeasures. In a recent survey, only 32% of organizations have insider threat solutions (Brenner, 2010). Insider attacks by employees and ex-employees account for 69% of security information attacks (Berinato, 2007, p. 4). The cost of including additional policy, procedures, IT infrastructure, and personnel to deal with insider threats is negligible compared to the costs caused by John Doe. Quarterly financial data revealed that revenues of RichFord Retail in Q2 2014 dropped by $3.5 million compared to Q2 2013, repair/recovery was an estimated additional $250,000, and lawsuits and legal fees will exceed $7.5 million. It has been estimated that implementation of security controls to prevent and mitigate malicious insider threats, including two new team members to form an insider response team, will cost $750,000 per year.

Recommendations

Recommendations to RichFord Retail Group are composed of 6 core components to predict and mitigate insider threats: (1) Insider Response Planning (IRP) for insider attacks; (2) Improving technical controls; (3) Improving administrative controls; (4) Implementing future mitigation strategies; (5) Ensuring Testing, Training, and Exercises (TT&E); and (6) Ensuring maintenance of IRP.

Incident Response Planning for Insider Attacks

This section focuses on modifications to the existing Incident Response Plan (IRP) to detect and prevent attacks from insiders and is based on the PDCERF model. PDCERF consists of six stages: (1) Preparation; (2) Detection; (3) Containment; (4) Eradication; (5) Recovery; and (6) Follow-up (Schultz and Shumway, 2001, p. 34).

Preparation

Senior management must be involved in all steps of preparation for insider attacks. The first step in preparing for insider threats is Risk Mitigation and Cost-Benefit Analysis. Risk Mitigation should follow the 9-step methodology defined in NIST 800-30 guidelines (see Appendix E, Figure 3: Risk Assessment Methodology Flowchart) (Stoneburner, Goguen, and Feringa, 2012, p. 9). Cost-benefit analysis should be performed to properly allocate resources and to improve security controls. Cost-benefit analysis should include: (1) Impact of implementing and not implementing new controls; (2) Estimation of implementation costs; and (3) Assessment of implementation costs and benefits against data criticality (Stoneburner, Goguen, and Feringa, 2012, p. 38).

Cybersecurity Insurance

Identity Theft Resolution Services, as part of Cybersecurity Insurance, protects organizations during data breach incidents. Cybersecurity Insurance policy will cover costs associated with notifying customers about the data breach incident, providing complimentary credit monitoring and credit counseling services (Singleton and Godes, 2012). Since Cybersecurity Insurance premiums are based on levels of self-protection, latest preventative security measures are to be implemented ("Cybersecurity Insurance", n.d.).

Legal Considerations

Legal considerations include compliance with all Federal, State, and Local laws and regulations. Mitigation of insider attacks and monitoring of employees are also important to consider from a legal perspective. Organization must consider a full range of disciplinary and legal actions (“A Preliminary Examination”, 2013, p. 9). It is critical to develop policies and procedures for effective legal efforts across jurisdictions, since many organizations may have contractors and/or employees that have ties to other countries (Schultz and Shumway, 2001, p. 403).

Insider Threat Mitigation Program

Insider Threat Mitigation Program establishes operational policies and procedures to deter, detect, and mitigate risk caused by insider attacks (McHugh, 2013, p. 1). This program must define mission and goals of the program, individual roles and responsibilities, operational procedures, strategic planning, and performance metrics (Gelles and Mahoutchian, 2012, p. 35). A robust Insider Threat Mitigation Program integrates non-technical data, such as behavioral analysis, with the technical data, such as monitoring of employees and threat intelligence (“A Preliminary Examination”, 2013, p. 5). Insider Threat Mitigation Program includes the monitoring of employees, which is accomplished by host-based user profiling and network-based sensors.

Educating Employees

Education and training classes provide situational awareness about insider attacks to all employees within the organization. Practical teaching tools and training classes have been used in the public and private sectors because they provide successful mitigation of insider attacks. IT personnel and senior management must know that they are highly susceptible to being recruited to steal company information (Cappelli, Moore, and Trzeciak, 2012, p. 122).

Designing and Instrumenting Networks

Designing and instrumenting networks has fundamental capability to prevent insider attacks. During network design, organizations should focus on inside and outside data flow. Since insiders have access to organization's systems, data, and other assets, creation of an insider-resilient network is challenging. Yet Another Flowmeter (YAF) and System for Internet Level Knowledge (SiLK) are two net flow sensors for development of long-term baseline of the network (“A Preliminary Examination”, 2013, p. 11). SiLK is an open source suite that collects, stores, and analyzes network flow data. As standard SiLK configuration is able to detect exfiltration of data through the Virtual Private Network (VPN) by detective flows of traffic over the network (Cappelli, Moore, and Trzeciak, 2012, p. 221-222).

Detection

The first step in detecting insider attacks is to understand the enemy and to know as many possible forms of attack that could be done. Phyo and Furnell discussed a method to have a detection oriented classification system for insider threats (Phyo and Furnell, 2004). This section presents three main areas to improve detection of insider threats: (1) Host-based detection; (2) Network-based prediction of malicious behavior using Automated Behavior Analysis (AuBa); and (3) Honeypots.

Host-based Detection

General computer user profiling can be categorized as such: (1) Command line calls issued by users; (2) System call monitoring for unusual application use/events; (3) Database/file access monitoring; and (4) Organization policy management rules and compliance logs (Salem et al., 2008, p. 73).

Salem et al. discussed and compared a number of methods for two-class based anomaly detection for insider attacks initiated from UNIX shell commands. According to Salem et al., a one-class approach is more appropriate for real world scenarios and several methods are discussed, such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Bayes classifiers. To detect insider threats for users performing UNIX shell commands, it is essential to look at frequency properties and to have the proper ordering of a chain of events (Salem et al., 2008, p. 73-78).

Effective methods for detecting malicious users in a Windows OS environment uses the following approaches: (1) Examination of process table data, which includes window behavior and commands executed via scripts; and/or (2) Window tracing that provides granular level information of command line and systems calls, while being fairly easy to reduce false-positive rates (Salem et al., 2008, p. 73-78).

Insiders may use a common browser to perform malicious activities. For detecting insider attacks involving websites, near perfect classification results can be obtained using SVM with simple features. Examples of simple features include the following: (1) IP address; (2) Timestamps; (3) HTTP methods (GET, PUT, POST, DELETE, etc.); (4) Requested pages; (5) Request status codes; and (6) Amount of data transferred. This method does not handle concept drift well or generalization of multiple users (Salem et al., 2008, p. 79-80). An alternative approach is to inspect outbound HTTP traffic using two different classic approaches, combining signature-based and anomaly-based detector with Hidden Markov Model (HMM) (see Appendix F, Figure 4: Two-step Detection For Web-based Insider Attacks) (Choi and Cho, 2012, p. 35-45).

Another area of exploit is programs that an insider may have authorization to install with intent to perform a malicious act. In a study about Probabilistic Anomaly Detection (PAD) algorithm, which is used to detect the misuse of registry keys in a Windows system, 100% detection rate of anomalies was detected with a 5% false positive rate (Stolfo, 2005, p. 659-693).

Network-based Prediction of Malicious Behavior

Insider threats can no longer rely on reactive security controls. Predictive proactive security can be accomplished by combining psychology and computer science. Predictive proactive security concepts are not theoretical, but instead are based upon validated technologies with a stellar success rate with over 20 years of research (Jackson, 2012, p. xxvii-xxviii).

Applied Behavior Analysis

It is possible to identify new and emerging malicious behavior using applied behavior analysis with three major components: (1) Antecedents identifying any event immediately before the interested behavior that is logically related to an occurrence of malicious behavior; (2) Behavior which is defined as the overt and observable action of an individual interested in predicting; and (3) A consequence, which is any event that occurs immediately after the interested behavior that is logically related to the occurrence behavior. Once a proper number of samples are recorded and analyzed, future behavior can be predicted (Jackson, 2012, p. 166-168).

Automated Behavior Analysis (AuBa)

AuBa is the automation and extension of applied behavior analysis for the purpose of predicting malicious behavior. These tools can construct predictive models 400 times faster than a manual process. AuBa does this by constructing predictive models from text-based reports of past behaviors that are manually created with Subject Matter Experts (SME) or automated processes using ThemeMate and AutoAnalyzer predictive modeling tools (Jackson, 2012, p. 357-367).

Using Inmate to Identify Insider Threats

InMate provides real-time identification of malicious insider threats using behavioral assessment of the internal network. This is done using two neural network-based assessment engines that convert internal user network traffic into validated measurements of intent and deception. This technology is deployed at SAIC and is officially called InMate Network Misuse Detection System. The advantage of InMate is its ability to look at 2100 combinations of monitored behaviors versus typical rules-based systems which have no more than a few thousand signatures. Blind validation tests show InMate to perform just as well as the best network intrusion experts in this field. Inmate has a very low false positive and low false negative occurrence rate (Jackson, 2012, p. 421-422).

Using Honeypots to Detect Insider Threats

Honeypots are traps set, usually in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) of an organization, to detect or provide countermeasures to unauthorized access of information systems. Honeypots can also be used to detect insider attacks. This can be done by placing honeytokens in the intranet that give perceived value. Since insiders know what information they want and usually where it is, placement of the honeytokens is vital. The honeytokens would direct the insider to honeypots that can further evaluate if the intention of the insider is malicious or not (Spitzner, 2003, p. 3-10).

Containment

Incident containment is the process where CSIRT takes steps to limit the scale and scope of an incident. Typically, if an incident is internal, affected systems are shut down. If an incident is external, all affected systems must be disconnected from the Internet and all applicable networks (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 270-271). Further containment actions include (1) Monitoring systems and network activities; (2) Disabling access to compromised systems; (3) Changing passwords and/or disabling accounts; and (4) Verifying that redundant systems have not been compromised (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 272). Furthermore, containment of insider-specific attacks usually involves coordination with law enforcement, search warrants, and probable cause affidavits. Implications with privacy violations during internal investigation of alleged insiders could be a concern (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 297).

Insider attacks typically involve registry keys, viruses, and other types of malware. Therefore, containment is very time-critical as it functions to prevent a further spread of malware. Containment is designed to outline predetermined strategies and procedures specific to a type of an insider incident (see Appendix G, Table 1: Possible Containment Strategies). NIST SP 800-61 Rev. 2 provides guidelines for containment of insider attacks. Containment is composed of three key components: (1) Choosing a containment strategy; (2) Conducting evidence gathering and handling; and (3) Identifying the attacking hosts (Cichonski et al., 2012, p. 36-37). Separate containment strategies should be implemented for low and high levels of traffic during an attack. For low-level traffic incidents, such as unauthorized access by an insider, first, sensor data should be aggregated and then a firewall should be used to filter out packets from the attacker's machine. For high-level traffic incidents, fusers are to be used to expand the rate controls from nearby filters to further ones (Batsell, Rao, and Shankar, 2006, p. 2). Containment usually consists of at least one of the following: (1) User participation; (2) Automated detection; (3) Disabling of services; (4) Disabling connectivity; and (5) Identification of infected hosts (Mell, Kent, and Nusbaum, 2012, p. 4-10).

Eradication

Eradication involves the removal of all traces of an attack, such as implanted rootkits and modified system logs (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 274). It is critical to identify all components that are directly and indirectly related to an incident and completely remove them. Vulnerability assessment and analysis must be done during the eradication phase to identify and research any open vulnerabilities (Mell, Kent, and Nusbaum, 2012, p. 4-18). NMap, Qualys, FoundScan are tools for vulnerability data collection. NIST SP 800-83 Rev. 1 guidelines provide industry standards for the eradication phase. As part of eradication, all infected hosts must be rebuilt. This includes installation and securing of the OS and applications, closing vulnerabilities, and restoring data from known good backups. The CSIRT will perform identification actions to identify still infected hosts and to gauge eradication success.

Recovery

Incident recovery is restoration of all affected systems to the pre-incident status as defined by the established backup and recovery plans. One of the most important elements of recovery is identification of data that may have compromised and/or disclosed by an insider. If disclosed data cannot be recovered, organizations must understand and analyze implications, such as disclosure of data, will have on future business operations (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 275). If containment, eradication and/or recovery are not successful, the Contingency Plan (CP) must be followed to escalate to the Disaster Recovery Plan (DRP) or Business Continuity Plan (BCP) (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 25-29).

Follow-up

The IRP follow-up process already in place needs to be amended to include the insider threat response team with specific policy and procedures for performing a postmortem analysis on each significant insider incident, findings of incident, lessons learned, and recommendations to handle insider threats. Documented insider incidents can train new team members on what mistakes were made to improve the overall security of the organization and must include re-evaluation and modification of an organization’s incident response procedures (Schultz and Shumway, 2001, p. 51-52).

Improving Technical Controls

Management and IT personnel are responsible for evaluating existing technical controls, and as needed, implementing new technical controls. Best practice is to evaluate and/or implement the following technical controls designed to combat insider threats: (1) Data Loss Prevention (DLP) and Information Loss Prevention (ILP) suites; (2) Discovery and classification tools; (3) Database security; (4) Application entitlements; (5) Removable media; and (6) Defensive search.

DLP/ILP Suites

Stolfo et al. discussed DLP/ILP suites, which prevent insiders from storage and transmission of confidential information in ways that violate organization’s security and/or privacy policies. Typically, DLP/ILP modules monitor for: (1) Data in motion via network perimeter traps, and email gateway filters; (2) Data at rest via host scans of databases, file shares, websites, and servers; and (3) Data in use via endpoint agents that monitor workstations. DLP/ILP suites should be configured to take the following immediate actions: (1) Report the incident; (2) Trigger immediate alert; (3) Destroy processes; (4) Relocate data; (5) Block data transmission; and (6) Encrypt data (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 61).

Discovery and Classification Tools

Data discovery entails identifying structured and unstructured data within the company's IT infrastructure and continuously tracking and monitoring of sensitive data in the company’s file shares, document repositories, databases, and email archives (Stone, 2009, p. 9). All sensitive company data should be categorized into five major categories: (1) Intellectual property; (2) Financial information; (3) Legal information; (4) Regulatory compliance; and (5) Personal privacy (Stone, 2009, p. 2). Once sensitive company data is discovered and classified, it is recommended to follow the Resource Description Framework (RDF) standards and its extensions Resource Description Framework Schema (RDFS) and Web Ontology Language (OWL). By implementing the RDF model and additional Semantic Web tools, organizations will have centralized data management, auditing, and change control of all sensitive information (Ben-David et al., 2010, p. 3).

Database Security

A major insider threat is based on exfiltration from the organization’s databases. To reduce risk, database security should involve the following multi-step process: (1) Aggressively enforcing access to the database on the need-to-know basis; (2) Ensuring consistent deployment of granular access controls in the database to reduce insiders read access to sensitive customer attributes; (3) Establishing granular database encryption (native and/or external) to reduce insiders visibility to sensitive attributes; (4) Implementing data-firewalls; (5) Restricting data extracts with sensitive data; (6) Using data masking to masquerade sensitive data values in extracts and reports; (7) Configuring audit logs to capture data access specifically for high-risk users (i.e. individuals who have access to the PII and (Personal Financial Information (PFI); and (8) Storing audit logs on separate servers (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 62). Database audit logs should be integrated with Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) correlation tool for effective centralized monitoring of security events at the database layer and correlation with other layers of organization’s IT infrastructure (Stolfo et al., 2008, 62).

Application Entitlements

Externalized Policy Entitlement decisions outside of business application prevent possible insider theft conducted by the organization’s IT personnel. OASIS eXtensible Access Control Markup Language (XACML) is an industry standard that enables entitlement enforcement on organization’s applications (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 62). As part of XACML, organizations implement and enforce authorization policies in terms of (1) Interchangeable policy format; (2) Support for authorization policies; (3) Procedures for conditional authorization; and (4) Policy combination and conflict resolution (Crampton, n.d., p. 5). Continuous application code reviews, source code controls, and configuration management control prevent “back doors” and logic bombs (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 63).

Removable Media

Ban on removable media, such as USB flash drives and Compact Disks (CDs), is effective in preventing intentional insider theft. Ban on removable media is to be enforced by organization’s policy and strict audits of attempted use of removable devices. All known removable media ports should be blocked on all employee workstations (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 73). Group Policy Objects (GPOs), Active Directory, and removable media audit events must be integrated with a SIEM system for analysis and correlation (see Appendix H, Figure 5: Instruction for Creating a New Auditing Policy) (Silowash and King, 2013, p. 5).

Defensive Search

Defensive Search is a forensic control to intercept already stolen sensitive information by either an insider or an outsider. Types of defensive searches are underground black market websites, FTP servers, bulletin boards/forums, and Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channels. Items to search for include credit and debit card numbers, customer addresses, and Social Security Numbers (SSNs). When doing a defensive search that involves PII, use regular expression matching to prevent leakage. Tools such as Google’s search API are available to search for PII without leaking it (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 63-64).

Implement/Improve Administrative Controls

Defense in depth strategies should be employed by adding administrative controls, which are designed to complement the technical controls proposed. Administrative controls include: (1) Policies; (2) Worker clearances; (3) Employee communication and training; (4) Database baselines and best practices; and (5) System of record audit (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 64-65).

Administrative Policies

Administrative policies discuss organization's policies and procedures for handling all data. All organization should have data classification categories. One example of categories to use is public, confidential, secret, or top secret. Once all data is classified, policies and procedures must define handling of data in terms of encryption, transmission, backup, and disposal (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 64).

Personnel Clearances

Personnel clearances, developed centuries ago by the military, is a system of clearance levels used to determine individual access to data. This basic system is a highly effective security control. Access of all personnel must be categorized as either (1) No clearance; (2) Confidential; (3) Secret; or (4) Top Secret (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 64).

Employee Communication and Training

Educational campaigns supported by a series of mandatory trainings about privacy, handling of organization’s sensitive data, and protection of customer information is an effective way to educate employees about proper conduct. This campaign is also effective in communicating new company policies and procedures. Regular training should be provided for the CSIRT, HR, and senior management about proper handling of disgruntled personnel, responding to suspicious behaviors, and dealing with negative performance reviews, which can prevent malicious insider incidents (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 65).

Database Baselines and Best Practices

Best practices for the database design are necessary to track access of authorized employees within the organization. Effective database design outlines: (1) Proper procedures for data scrubbing; (2) Appropriate use of faceless application IDs; (3) Implementation of security access controls; (4) Use of database views following need to know policies; and (5) Encryption of all sensitive data (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 65).

System of Record Audits

System of record monitors and records actions of employees within organization’s databases and related infrastructure. System of record audits allow flexible monitoring based on individual actions, such as type of SQL statement executed, or monitoring based on combination of factors, such as user name and/or specific application parameters ("Oracle Database Security Guide", 2006). Audit trails have the capability to provide additional information about access control and certification processes of production databases. System auditors must have necessary knowledge of database design and internal reporting procedures in case of detection of potential insider incidents (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 65).

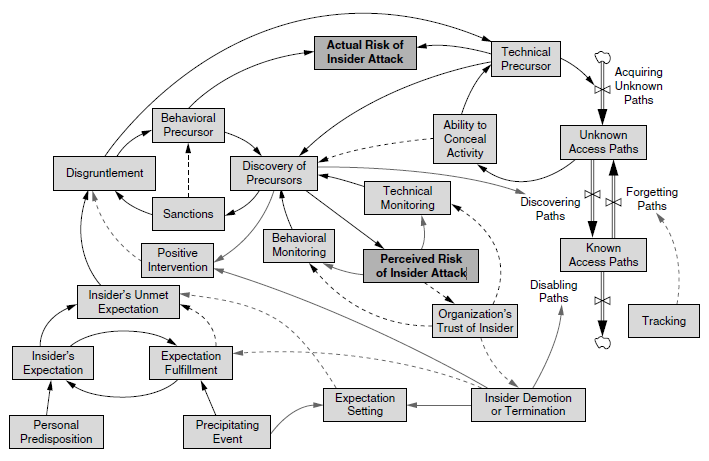

Future Mitigation Strategies

Advanced mitigation strategies integrate behavioral psychology and information security. Such integration can improve the resilience of organization’s infrastructure and is capable of mitigating insider threats at early phases. It is critical for senior management to recognize and acknowledge mitigation strategies to combat insider threat.

Early Mitigation Through Setting of Expectations

Regular communication between senior management and employees is a first step in creating a healthy professional environment and setting proper expectations. Senior management must be able to set expectations and address personal predispositions of employees. This lowers the rate of disgruntlement by minimizing possibility of unmet expectations (Cappelli, Moore, and Trzeciak, 2012, p. 47). If employees accumulate levels of unmet expectations, then there will be disgruntlement, which is a key motivator of insider attacks. Organizations should conduct regular employee reviews, self-assessments, and as necessary, take actions to address employee dissatisfaction (Cappelli, Moore, and Trzeciak, 2012, p. 49).

Handling Disgruntlement Through Positive Intervention

Training and educational classes to the senior management focusing on disgruntled employees and concepts of human behavior, such as behavioral precursors and positive intervention, are effective in lowering disgruntlement of potential insiders (see Appendix I, Figure 6: Issues of Concern Leading to an Insider Theft). This requires managers to be trained about human psychology and detecting signs of potential problems (Cappeli, Moore, and Trzeciak, 2012, p. 49). Employee Assistance Program (EAP) is a system of positive intervention that utilizes experienced psychologists who assist employees in dealing with personal and work-related issues. Optionally, EAPs can include counseling services to employees and their family members (Stolfo et al., 2008, p. 31).

Eliminating Unknown Access Paths

Immediate elimination of access paths to terminated employees prevents unauthorized access and leakage of company data. Careful tracking, logging, and monitoring of access paths of employees, business partners, and contractors allow control of access paths. Unknown access paths include backdoor accounts, shared accounts, remote access, malicious code introduced by an insider, and logic bombs (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 50). Organizations should develop policies, procedures, and operating standards to effectively (1) Manage all privileged access paths; (2) Audit and control all access paths; and (3) Research and eliminate unknown access paths (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 50-51).

More Complex Monitoring Strategies

Enterprise Software Configuration Management (SCM) and Change-managements software are highly effective at preventing logic bombs installed by insiders. SCM and Change-management software trigger an alert when any of the critical files are modified. Since critical files are modified infrequently, if ever, an alert will be triggered upon file modification (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 53).

Risk-Based Approach to Prioritizing Alerts

Organization's data should be prioritized by using a risk-based approach. By prioritizing all critical files and integrating them with SCM and Change-modification software, CSIRT can efficiently analyze and investigate suspicious malicious insider activity. Additionally, source code reviews of all production systems, which is commonly neglected in the industry, is effective at preventing malicious unauthorized insider attacks (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 53-54).

Targeted Monitoring

A well-designed targeted monitoring system is effective in preventing malicious insider activity. Targeted monitoring involves monitoring and logging of network and server activity of a randomly chosen group of employees and/or employees with poor performance. Well defined policies must in place prior to any targeted monitoring. The legal department should be involved from the beginning to assure that all take actions are legal and comply with Federal, State, and Local laws (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 55).

Measures upon Demotion or Termination

According to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, 33% of information security attacks originated from internal employees, while 28% of attacks originated from ex-employees and/or partners (Berinato, 2007, p. 4). This study suggests that a clearly-defined process for handling demotions and terminations is highly effective at preventing possible insider attacks. IT personnel must be actively engaged throughout the process of demotions and terminations (see Appendix J, Figure 7: Measures upon Demotion or Termination). During the termination process, IT personnel must immediately eliminate all known access paths to prevent future unauthorized access. During the demotion process, IT personnel must immediately analyze all roles and responsibilities of the new position, update authorization levels and access controls, and updating role-based access (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 56).

Securing System Logs

System logs, including remote access, file access, database, application, and email logs, are commonly used to identify malicious insiders. However, technically savvy insiders are able to modify system logs to cover their tracks. Therefore, system logs must be secured. The most efficient way to secure system logs and to protect their integrity is by using continuous logging to a centralized secure server (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 56-57).

Ensure Testing, Training, and Exercises

A TT&E plan needs to have mechanisms in place to ensure effectiveness and to help with the maintenance management. The TT&E plan should have steps in place for the following: (1) Make sure that personnel are properly trained for their roles and responsibilities; (2) The plan is exercised to validate feasibility; and (3) Systems and components are tested to ensure they operate properly in the context of the TT&E plan. The TT&E plan should document all components of the program and all information related to the program are also documented. In addition to a TT&E plan, the following components are necessary to have a complete TT&E program: (1) Policy; (2) Identify roles and responsibilities; (3) Establish a schedule; and (4) Document methodology (Grance et al., 2014, p. 2-2).

Testing, Training, and Exercises Policy

There are three main steps to develop a TT&E policy. The first step is to have a champion in senior management and make sure that the champion is involved. The second step is for the champion to understand the program thoroughly and provide the necessary resources to the program to succeed. The third step is to assure that the champion is aware of organization’s benefits and risks. NIST SP 800-84 provides a recommended list of elements to include in a TT&E policy: (1) Purpose; (2) Effective date; (3) Objectives; (4) Applicability and scope; (5) Authorities and related policies; (6) Roles and responsibilities of key business units and staff positions; (7) TT&E requirements; (8) TT&E review and approval; (9) Enforcement and compliance; (10) Points of contact for additional information; and (11) Definition of terms (Grance et al., 2014, p. 2-3).

Identify Roles and Responsibilities

The TT&E program should be managed by staff that are directly responsible for the organization’s IT capabilities and program coordination. The TT&E program coordinator has overall responsibility of the TT&E plan and events. The TT&E program coordinator will report to the IT Plan coordinator, who in turn reports to the Office of the Chief Information Officer (CIO) (Grance et al., 2014, p. 2-4).

Establish Overall Schedule

The TT&E plan needs to schedule and document the projected dates for each activity in the TT&E program. This should be done at least once a year (Grance et al., 2014, p. 2-4).

Document Methodology

The document methodology to follow, as recommended by NIST SP 800-84, includes four main phases: (1) Design the event; (2) Develop event documentation; (3) Conduct the event which can be training, exercise or a test; and (4) Evaluate lessons learned from the event to include appropriate documentation and modifications to the TT&E plan (see Appendix K, Figure 8: TT&E Event Methodology) (Grance et al., 2014, p. 2-5).

Training, Exercises and Tests

Training is an ongoing process, which allows staff to maintain and enhance their skills to keep up with new emerging technologies. NIST SP 800-50 and NIST SP 800-16 provide details on training programs and events (Grance et al., 2014, p. 3-1). Exercises need to be performed to verify that all scenarios are covered properly. A number of ways exist to test an implemented IRP are: (1) Desk check; (2) Structured walk-through; (3) Simulation; (4) Parallel testing; (5) Full interruption; and (6) War gaming (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 145-146). Tests use evaluation tools that have quantifiable metrics to make sure that an IT system or component is operating as expected, and can come in one of three forms: (1) Component testing; (2) System testing; and (3) Comprehensive testing (Grance et al., 2014, p. 6-1).

Ensure Incident Response Plan Maintenance

The IRP must be maintained in a state that reflects system requirements and related procedures, organizational structure, and policies. Factors such as evolving business needs, technology upgrades, and policy changes will require the IRP to be reviewed and updated continuously (Swanson et al., 2010, p 31).

It is vital to include an After-Action Review (AAR). The AAR provides a detailed log of an incident from the first time it was detected through the final recovery procedure step. The AAR should be done as soon as possible post-incident recovery and involve all members who took action during the incident. AAR team members can review the handling of an incident and provide lessons learned on if CSIRT responded to the incident properly or if the IRP needs to be updated to cover a new type of incident. In the case of the RichFord insider attack, additional documentation can be added to the IRP to be better prepared for a future insider attack. The AAR also serves as: (1) A historical record of events that may be required for legal proceedings; (2) A case study training tool, which serves as part of the “know yourself” philosophy; (3) A way to have a closure to an incident (Whitman, Mattord, and Green, 2013, p. 317-318).

Conclusion

Insider attacks account for 69% of all information security attacks (Berinato, 2007, p. 4). The security plan of RichFord Retail Group focused on preventing external threats and it lacked security controls for insider threat detection and prevention. RichFord Retail is not unique in this problem, with 68% of organizations having no insider threat solutions (Brenner, 2010).

The insider attack on RichFord Retail group, executed by John Doe, caused severe damage financially and will have a negative impact on their reputation for years to come. The loss analysis and lessons learned revealed that the costs from this insider attack far exceed the extra security measures required to detect and prevent it. Recommendations entailed the modification to the current IRP PDCERF. The recommended modifications to the PDCERF will allow RichFord Retail Group to be confident in its ability to detect and mitigate potential future insider threats. Keeping senior management involved, conducting employee awareness training, and monitoring employees within the allowance of Federal, State, and Local laws are essential.

Advanced detection techniques, such as Automated Behavior Analysis and Honeypots using Honeytokens, are at the forefront on insider detection technology and further research study in this area to quantify effectiveness is suggested. Solutions to improve both technical and administrative controls are provided in order to properly prevent and secure PII and company confidential data not only from external threats, but also malicious, accidental, and naively coerced insider threats.

Future mitigation strategies for handling demotions and denial of promotions are provided as this is a common source of insider threat, and it specifically pertains to the John Doe incident. TT&E and IRP maintenance solutions are discussed. RichFord Retail Group had old documentation and no testing, training or exercise procedures in place. Further research needs to be done by RichFord Retail Group to determine the proper set of recommendations to implement in support of an updated Risk Management and Contingency Plan that takes insider threats into account.

References

"A Preliminary Examination of Insider Threat Programs in the U.S. Private Sector." NIST.gov - Computer Security Division - Computer Security Resource Center. INSA, Sep 2013. Web. 25 March 2014. <http://csrc.nist.gov/cyberframework/framework_comments/20131213_charles_alsup_insa_part4.pdf>.

Baracaldo, Nathalie, and James Joshi. "A trust-and-risk aware RBAC framework: tackling insider threat." Proceedings of the 17th ACM symposium on Access Control Models and Technologies. ACM, 2012.

Batsell, Stephen G., Nageswara S. Rao, and Mallikarjun Shankar. "Distributed intrusion detection and attack containment for organizational cyber security." Oak Ridge National Laboratory, n.d. Web. 4 April 2014. <http://www.ioc.ornl.gov/projects/documents/containment.pdf>.

Ben-David, David, Tamar Domany, and Abigail Tarem. "Enterprise Data Classification using Semantic Web Technologies." ISWC 2010. n.p., n.d. Web. 26 Mar. 2014. <http://iswc2010.semanticweb.org/pdf/402.pdf>.

Berinato, Scott. "The Global State of Information Security." PricewaterHouseCoopers. CXO Media, 1 Jan. 2007. Web. 15 Apr. 2014. <http://www.pwc.be/en_BE/be/publications/state-of-infsecurity-pwc-07.pdf>.

Brenner, Bill. "Companies on IT Security Spending: Where's the ROI?." CSO Online. CXO Media, Inc., 25 Jan 2010. Web. 30 March 2014. <http://www.csoonline.com/article/2124757/metrics-budgets/companies-on-it-security-spending--where-s-the-roi-.html>.

Cappelli, D., Moore, A., and Trzeciak, R. (2012). The CERT guide to insider threats: How to prevent, detect, and respond to information technology crimes. (1 ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley, 2012. Print.

Choi, Byungha, and Kyungsan Cho. Detection of insider attacks to the web server. Journal of Wireless Mobile Networks, Ubiquitous Computing, and Dependable Applications 3.4. 2012.

Cichonski, Paul, Tom Millar, Tim Grance, and Karen Scarfone. “National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Special Publication 800-61 Revision 2: Computer Security Incident Handling Guide”. National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2012. Web. 3 April 2014. <http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-61rev2/SP800-61rev2.pdf>.

Crampton, Jason. "XACML and Role-Based Access Control." DIMACS Workshop on Secure Web Services and e-Commerce. Royal Holloway, University of London, London, UK, n.d. Web. 19 March 2014. <http://dimacs.rutgers.edu/Workshops/Commerce/slides/crampton.pdf>

“Cybersecurity Insurance”. Department of Homeland Security Publications. Department of Homeland Security. n.d. Web. 27 March 2014. <http://www.dhs.gov/publication/cybersecurity-insurance>.

"Digital Forensic Analysis Methodology." Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS) - Cybercrime Lab. Department of Justice, 22 Aug. 2007. Web. 15 Apr. 2014. <http://www.justice.gov/criminal/cybercrime/docs/forensics_chart.pdf>.

Gelles, Michael, and Tara Mahoutchian. "Mitigating the Insider Threat: Building a Secure Workforce”. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Deloitte, Mar. 2012. Web. 26 March 2014. <http://csrc.nist.gov/organizations/fissea/2012-conference/presentations/fissea-conference-2012_mahoutchian-and-gelles.pdf>.

Grance, Tim, Tamara Nolan, Kristin Burke, Rich Dudley, Gregory White, and Travis Good. "NIST 800-84, Guide to Test, Training and Exercise Programs for IT Plans and Capabilities." NIST.gov - Computer Security Division - Computer Security Resource Center. National Institute of Standards and Technology, n.d. Web. 1 Apr 2014. <http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-84/SP800-84.pdf>.

Jackson, Gary M. Predicting Malicious Behavior: Tools and Techniques for Ensuring Global Security. John Wiley & Sons, 2012. Print.

McHugh, John M. “Department of Defense. Army Directive 2013-18 (Army Insider Threat Program)”. Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2013. Web. 5 April 2014. <http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/army/insider.pdf>.

Mell, Peter, Karen Kent, and Joseph Nusbaum. “National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Special Publication 800-83: Guide to Malware Incident Prevention and Handling”. NIST.gov - Computer Security Division - Computer Security Resource Center. National Institutes of Standards and Technology, 2012. Web. 12 April 2014. <http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-83/SP800-83.pdf>.

"Oracle Database Security Guide." Database Auditing: Security Considerations. Oracle, 1 May 2006. Web. 9 April 2014. <http://docs.oracle.com/cd/B19306_01/network.102/b14266/auditing.htm

Phyo, A. H., and S. M. Furnell. "A detection-oriented classification of insider it misuse." Third Security Conference. 2004. Print.

Salem, Malek Ben, Shlomo Hershkop, and Salvatore J. Stolfo. A survey of insider attack detection research, Insider Attack and Cyber Security. Springer US, 2008. Print.

Schultz, Eugene, and Russell Shumway. Incident Response: A Strategic Guide to Handling System and Network Security Breaches. New Riders Publishing, 2001. Print.

Silowash, George, and Christopher King. "Insider Threat Control: Understanding Data Loss Prevention (DLP) and Detection by Correlating Events from Multiple Sources." Pittsburgh, PA: 2012. <https://www.sei.cmu.edu/reports/11tn024.pdf>.

Singleton, Kristi, and Scott Godes. "Top Ten Tips for Companies Buying Cyber Security Insurance Coverage." ACC. Association of Corporate Counsel, 12 Dec. 2012. Web. 13 April 2014. <http://www.acc.com/legalresources/publications/topten/tttfcbcsic.cfm>.

Spitzner, Lance. "Honeypots: Catching the insider threat." Computer Security Applications Conference, 2003. Proceedings. 19th Annual. IEEE, 2003. Print.

Stolfo, Salvatore, et al. Insider Attack and Cyber Security: Beyond the Hacker. 2008. Fairfax, VA: Springler, 2008. Print.

Stolfo, Salvatore J., et al. A comparative evaluation of two algorithms for windows registry anomaly detection. Journal of Computer Security 13.4 2005. Print.

Stone, Michael. "Data Discovery and Classification in Five Easy Steps." 2009. <http://trendedge.trendmicro.com/pr/tm/te/document/DLP_Data_Discovery_and_Classification_in_5_Steps_090630.pdf>.

Stoneburner, Gary, Alice Goguen, and Alexis Feringa. “NIST Special Publication 800-30: Risk Management Guide for Information Technology Systems”. NIST.gov - Computer Security Division - Computer Security Resource Center. National Institutes of Standards and Technology, 2012. Web. 15 April 2014. <http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-30-rev1/sp800_30_r1.pdf>.

Swanson, Marianne, Pauline Bowen, Amy Wohl Phillips, Dean Gallup, and David Lynes. "Contingency Planning Guide for Federal Information Systems”. NIST.gov - Computer Security Division - Computer Security Resource Center. National Institutes of Standards and Technology, 2010. Web. 30 Mar 2014. <http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-34-rev1/sp800-34-rev1_errata-Nov11-2010.pdf>.

Vijayan, Jaikumar. “FTC can sue companies hit with data breaches, court says.” Computerworld. Computerworld Inc., 10 Apr 2014. Web. 14 March 2014. <http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9247577/FTC_can_sue_companies_hit_with_data_breaches_court_says>.

Whitman, Michael, Herbert Mattord, and Andrew Green. Principles of incident response and disaster recovery. Cengage Learning, 2013. Print.

Appendix A

Company Profile

Company name: RichFord Retail Group Inc.

Founded: 2001

Industry: sporting goods eCommerce retailer

Products: sports apparel, equipment, footwear, and exercise equipment

Number of Employees: 400

2013 Revenue: $300 million

Number of customers: over 10 million

Number of Facilities: headquarters and distribution center located in Rockville, MD

Appendix B

Assumptions

- RichFord Retail Group is a fictitious company. All company profile information and attack details were created by the authors for purposes of simulation for this insider attack research paper. All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

- Statistics about quarterly drop in revenue, repair/recovery costs, and lawsuits and legal fees are fictitious for the purpose of this scenario.

- There is an in-house Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT) to respond to incidents 24/7 and 365 days a year.

- A Risk Management Framework (RMF) has been implemented that follows NIST SP 800-37 Rev. 1 guidelines.

- An Incident Response Plan (IRP) has been implemented that follows NIST SP 800-61 Rev. 2 guidelines. However, the IRP did not cover insider threats.

- A Business Continuity Plan (BCP) has been implemented that follows NIST 800-34, Rev. 1 guidelines.

- A Disaster Recovery Plan (DRP) has been implemented following the best practices and industry standards.

- A Business Impact Analysis (BIA) has been implemented that follows NIST SP 800-34 Rev. 1 guidelines.

- A Contingency Plan (CP) has been implemented that follows NIST SP 800-34 Rev. 1 guidelines.

- An Incident Response Lab has been implemented at RichFord Retail Group.

- NIST 800-53 Rev. 4 has been implemented with proper impact analysis and risk assessment prior to taking defensive measures. However, implemented security used did not cover insider threats.

- There is a guest wireless network, but has no connections to RichFord Retail Group’s infrastructure. The guest wireless network has been implemented according NIST SP 800-153 guidelines.

- Audit logs were stored on external servers that John Doe did not have access to.

- Stolen data has not been found on black market forums and law enforcement is taking the lead on this investigation.

- Testing, Training, and Exercises (TT&E) of Incident Response Plan did not exist prior to the incident.

- Maintenance of the Incident Response Plan did not exist prior to the incident.

- There was no Cybersecurity Insurance coverage for Identity Theft Resolution Services.

- Corporate policy has employee’s read, understand and agree to monitor and search of work computers and included recurring notifications for all network and system banners to remind users monitoring and searching may occur.

- An After-Action Review was not performed.

Appendix C

Figure 1: RichFord Retail Group Network Topology Overview

Appendix D

Figure 2: Overall flow of digital investigation ("Digital Forensic Analysis Methodology”, 2007)

Appendix E

Figure 3: Risk Assessment Methodology Flowchart (Stoneburner, Goguen, and Feringa, 2012, p. 9)

Appendix F

Figure 4: Two-step Detection For Web-based Insider Attacks (Choi and Cho, 2012, p. 38)

Appendix G

Strategy Description

|

Shutting a system down altogether (a drastic, but sometimes very advisable, decision to prevent further loss and/or disruption).

|

Disabling or deleting login accounts that have been compromised.

|

Increasing the level of monitoring of system and/or network activity.

|

Setting traps such as decoy servers.

|

Disabling services, such as file transfer services, if vulnerabilities in services are being exploited.

|

Striking back at the attacker’s system(s), although you should in general avoid doing this and should never do this without the explicit approval of top-level management.

|

Disconnecting from a network. This at least allows local users to obtain some level of services, although it will prove disruptive.

|

Changing the filtering rules of any firewalls and routers to exclude traffic from hosts that appear to be launching the attacks.

|

Table 1: Possible Containment Strategies (Schultz and Shumway, 2001, p. 99-100)

Appendix H

Figure 5: Instruction for Creating a New Auditing Policy (Silowash and King, 2013, p. 6)

Appendix I

Figure 6: Issues of Concern Leading to an Insider Theft (Cappeli, Moore, and Trzeciak, 2012, p. 48)

Appendix J

Figure 7: Measures upon Demotion or Termination (Cappeli et al., 2012, p. 29)

Appendix K

Figure 8: TT&E Event Methodology (Grance, Nolan, Burke, Dudley, White, and Good, 2014, p. 2-5)

No comments:

Post a Comment